Brophy and the Board of Trustees felt that the Institute would live happily ever after

when the bill making the Institute a state institution was signed.

Brophy and the Board of Trustees felt that the Institute would live happily ever after

when the bill making the Institute a state institution was signed.

Then came the historic evening of Feb. 21, 1950, when fire struck, virtually destroying the Institute. The fire was a surprise, but it was not without premonition.

W.N Ferris had always been deathly afraid of fires. He wouldn't even burn trash unless someone was standing by holding a garden hose ready to put out the blaze should it get out of control. He had kept the school heavily insured.

The frame structure known as the Music Building, which also housed the Institute's

cafeteria, had burned in the 1920's, and the insurance money had gone into the Alumni

Building. Opponents of the 1943 sale of the school to the state had pointed out that

the buildings (except the  Alumni Building) were firetraps. The Mail Building had been minimally wired for its

first electric lights. As new circuits were needed, wires were strung helter skelter

criss-crossing each other like a lattice, especially in the attic. This haphazard

circuitry had been repaired in 1947, but a lot of people didn't know it. False rumors

still persist that the fire was caused by that faulty wiring.

Alumni Building) were firetraps. The Mail Building had been minimally wired for its

first electric lights. As new circuits were needed, wires were strung helter skelter

criss-crossing each other like a lattice, especially in the attic. This haphazard

circuitry had been repaired in 1947, but a lot of people didn't know it. False rumors

still persist that the fire was caused by that faulty wiring.

The fire was first noticed about 5:15 p.m. when Melvin Dunn, the night janitor, and Karl Merrill, who was then dean of Commerce, smelled smoke at different points in the building. Dunn went to Merrill's office to ask him to call the fire department, but Merrill had already called. Both men set out with fire extinguishers to one of the obsolete air shafts which had been originally designed to control the odors from the toilet rooms.

It was the last day of the winter term. The secretaries had just left the building. The band had been practicing, the playhouse group had been rehearsing and the graduates of that winter term had just been feted by the president at a graduation reception. None seemed concerned or too eager to get out of the building even after the alarm sounded. President Brophy, returning from the reception, assumed it was a fire drill.

But by the time Dunn got back to the attic to see if he could control the fire from that end, the smoke was too thick for him to enter.

By then there was general confusion. Some of the group, including Brophy, went into the men's toilet room to try to get into the ventilator shaft from the bottom. The door to the unused ventilator had recently been nailed shut and Brophy tried to break it in by kicking it with his artificial foot, but to no avail. The men did finally get the shaft open and extinguished the blaze in the base of the shaft, but the updraft had carried the fire up to the other floors, including the attic, and the fire and smoke were spreading rapidly.

It was a cold, icy day with the high temperature only 13 degrees F. The fire department had trouble getting its equipment over the slippery streets; and by the time the engines arrived, flames had spread throughout the Main Building.

Looking over the remains is faculty member Roy Newton.

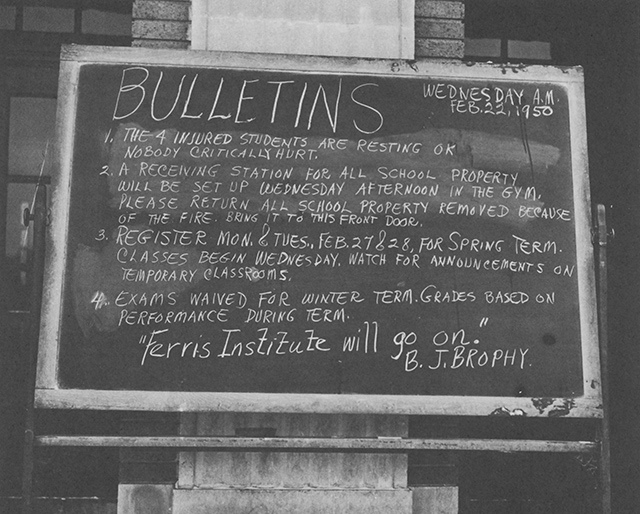

Looking over the remains is faculty member Roy Newton.There were many students around volunteering to help get equipment and records from the building. Four students were hurt -- Richard Kiebler, Robert Andrews, Kenneth Kocher, and James McEvoy -- but not seriously.

Several other students volunteered to go into the Pharmacy Building, which had not yet caught fire, to try to rescue the books from the Library which was housed on the top floor of that building, but the police stopped them.

Before long the fire had jumped an enclosed passageway at the second and third floor levels to the Pharmacy Building which was separated from the Main Building by about 20 feet. That building was soon engulfed in flames.

The main entrance of Old Main.

The main entrance of Old Main.The fire department was hampered by extremely low water pressure. (After the fire, the water tower was installed near the campus at the corner of State and Cedar Streets, to forestall any other such accidents.) By 7:45 p.m. the fire was under control, but was still burning at 10 p.m. Firemen played water on the ruins all night long.

The light from the fire attracted people from miles around. Though the night was bitterly cold, the curiosity seekers could not get very near the blazing buildings because of the heat the blaze was generating.

It was a sad crowd which watched that fire. Many observers were Ferris alumni; others were Ferris employees. As a fireman said later, "There wasn't a dry eye in the house." By morning nothing was left but a pile of smoldering ruins.

The fire marshal's report concluded that the fire was started by some students, careless

with their smoking, in the smoking room just off the toilet rooms. After all, it was

the last week of school for the term, and the students were "horsing around" as students

sometimes do at the term's end.

The fire marshal's report concluded that the fire was started by some students, careless

with their smoking, in the smoking room just off the toilet rooms. After all, it was

the last week of school for the term, and the students were "horsing around" as students

sometimes do at the term's end.

The air vent, which had been considered such a modern innovation in 1894, served as a "chimney" and sucked the heat from a small piece of charring wood up the shaft. Opening all the doors into the shaft probably didn't help much.

After all these years, rumors still persist that the fire was  started by an arsonist, and that the fire started at the top of the building.

started by an arsonist, and that the fire started at the top of the building.

Laboratory technicians who tested the charred wood for the fire marshal could find no trace of petroleum distillates in their samples. Some of the samples had a strong smell of burned matches, but no trace of phosphorus could be detected. There was a strong trace of phosphate in one of the beams indicating that at some time, probably while it was laying on the ground in the building stage, the beam had been soaked with some kind of chemical, but not a flammable one.

Two incidents further fanned the pyromania theory.

| Previous | Next |